Composite Amber with an Unusual Structure

With amber emerging as one of the most popular gems in the Chinese jewelry market, the quality of imitations also appears to be on the rise. Many of these simulants are composites consisting of two or more substances, such as amber, copal, artificial resin, and plastic, joined together as a finished piece. Some composites incorporate small amber fragments. Manufacturers may also embed insect or lizard inclusions (Winter 2005 GNI, pp. 361–362). One notable composite amber specimen, a polished pebble-shaped pendant (figure 1), was recently identified at the National Gemstone Training Center (NGTC) lab in Beijing.

This specimen displayed no clear plane separating the two materials; instead there appeared to be an intersecting mixture of amber and polymer resin. The natural amber core had been covered by an outer shell of polymer resin, and about one-third of the natural amber was still exposed. Some of the small exposed portions were large enough for examination and identification. The most interesting aspect of the specimen was its pair of insect inclusions, one occurring naturally and the other artificially (figure 2).

The specimen had a waxy luster. Reflected light displayed scratches on the surface, suggesting a low hardness. It was relatively easy to observe the boundary between the natural and artificial resin sections using reflected light. Unlike most intersections found in such pieces, there were no air bubbles or other features, only clear lines. We also saw some small circular areas using transmitted and reflected light. These proved to be natural amber sections, both on the surface and within the sample, that had been polished and exposed during fashioning. The entire structure of this specimen was an intersection of two substances, identified as natural amber and polymer resin.

Observed under the microscope with transmitted light, part of the sample showed reddish brown curved lines; these were flow lines from natural amber. The two parts of the composite were clearly visible. The top part consisted of natural amber with a naturally deposited insect inclusion. The insect was translucent and partially broken. The larger insect inclusion in the bottom part was in much better condition, with an opaque transparency and clearer outline. The air bubbles around the larger insect were more spherical and concentrated, which is not typically seen in natural amber.Under UV light, the composite gave an uneven fluorescence to long- and short-wave UV. The amber part showed a blue-white fluorescence, while the artificial resin fluoresced yellowish green.

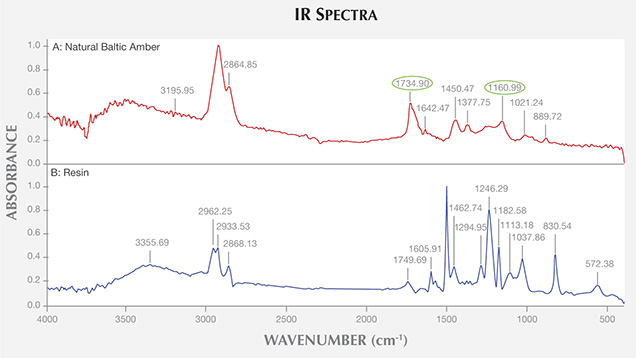

To confirm the identity of the two different materials, we analyzed their infrared spectra (figure 3). Spectrum A displays main peaks at 1734.90 and 1160.99 cm–1, typical of Baltic region amber. Spectrum B shows a series of peaks; after comparison with spectra of amber, copal and some other synthetic materials, we used spectrum B to identify this sample as polymer resin. With its combination of natural and imitation amber, accompanied by natural and artificial insect inclusions, the piece presented an interesting identification study.