Oregon Sunstone Update

At the GJX Show, Nirinjan Khalsa (Suncrystal Mining, Lake and Harney Counties, Oregon) showed us a remarkable 35.50 ct rich orangy red Oregon sunstone fashioned into a modern mixed-cut cushion by lapidary Jean-Noel Soni (Top Notch Faceting). This stone (figure 1) resembled a fine ruby under the showcase lights and was one of the most exquisite examples we had seen.

At Khalsa’s request, we followed up with Soni after the show. He told us the original rough weighed 198.82 ct. As is typical with Oregon sunstone, the rough contained spots of strong red or green color in the cores of otherwise yellow or near-colorless crystals. This crystal had two color spots, so he divided it, and this gem was the first of two he intended to cut. Rather than using CAD software to design his gems’ faceting styles, Soni treats each rough as unique and individual, cutting to maximize color and luster. He explained that the pavilion had to be deep, due to sunstone’s relatively low RI (1.563–1.572). This produced a 63.00 ct preform, from which he faceted the 35.50 ct gem we saw. The asking price for this gem—reportedly from one of the mines on Little Eagle Butte (in Harney Basin, near Plush, Oregon)—was in the region of $60,000.

Also at the GJX show, Don Buford and Mark Shore (Dust Devil Mining, Plush, Oregon) gave an update on their operations. They said 2014 was a good year at Dust Devil. They uncovered a former dried creek bed where the basalt was extensively decomposed, which has allowed easier recovery of the sunstones. Buford hopes to have the mine’s optical sorter operational for the 2015 mining season.

Shore showed us an exceptional 156.00 ct “watermelon” sunstone from recent production (figure 2). The stone has a red center surrounded by a greenish “rind.” Shore has made arrangements to have it carved by Dalan Hargrave, winner of multiple AGTA Spectrum Awards.

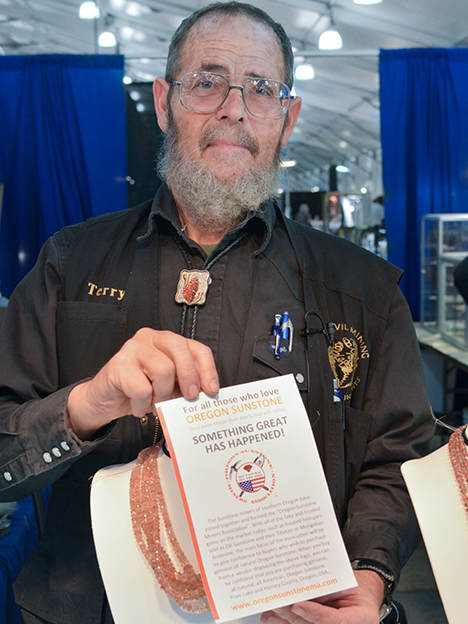

At the 22nd Street show, Terry Clarke, co-owner of the Dust Devil mine, explained a recent initiative to maintain the integrity of natural, untreated Oregon sunstone and promote it to retailers and consumers as a rare and desirable “all-American” gemstone. Called the Oregon Sunstone Miners Association (OSMA), the organization includes most of the miners with working claims or mines in Lake and Harney Counties (figure 3). OSMA also offers an associate membership for sellers of loose gems or jewelry. Anyone purchasing sunstone from an OSMA member can be assured they are getting the natural, untreated Oregon product. The intention is to expand the marketplace for this unique gem and maintain stability and consumer confidence in the event of an influx of treated material from another source. The association’s website is www.oregonsunstonema.com.

At the AGTA show, John Woodmark (Desert Sun Mining & Gems, Depoe Bay, Oregon) provided an update of his operations at the Ponderosa mine and summarized the current market for his goods. He showed us a striking 2.77 ct “spinel red” gem from recent production (figure 4).

According to Woodmark, 2014 saw heightened interest in Oregon sunstone. He received requests for rough from clients in Australia and for finished stones from Brazil and Europe (principally the UK and Germany). At this particular show, Woodmark said he had received many more inquiries from domestic jewelers for samples and information, all following customer requests due to growing public awareness of the gem. He cited a TV shopping channel’s recent promotion of production from the Sunstone Butte mine and the growing reach of his Internet business. For more information on the Sunstone Butte mine, see www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-butte-sunstone.

Woodmark observed that Internet merchandising, often by TV jewelry shopping channels, has been transformative for low-volume, one-of-a-kind products like Oregon sunstone. Web marketing frees traditional TV merchandisers from the production costs of on-air hosts and studios, and allows the cost-effective presentation of a spectrum of Oregon sunstone from “bargain parcels” to unique designer cuts costing several thousands of dollars per piece. According to Woodmark, one buyer for a major TV jewelry retailer at the Tucson shows said that Internet business was now 40% of the company’s total sales volume.

Woodmark estimated the total volume of fashioned Oregon sunstone on the market in 2014 was approximately 70,000 carats. By his calculations, that would be sufficient to supply one large U.S. retail jewelry chain with 10 carats per store per month over the course of a year. If demand picks up in 2015, that volume will not meet the industry’s needs. Woodmark reported that business was up 25% on the previous year’s show, which was up one-third on the year before.

In the 2014 mining season, Woodmark employed up to five pickers working the screens. He worked the mine for a total of 20 days and produced almost 2,000 kg of rough in all grades. Woodmark plans to work for 40 days in 2015 and expects to recover 4,000 to 5,000 kg of rough. To start the upcoming mining season, Woodmark will bring in heavier machinery and extend the pit back into the hillside. He will also bring in a bulldozer with a ripper to tear up the pit floor and start moving downward, too. Late 2014 saw recovery of larger rough, some pieces up to 70 grams (figure 5). In addition, the pit’s “red zone,” with a higher proportion of red-cored rough (up to 20%), remained productive. Woodmark expected the trend of bigger, better stones to continue as the miners work deeper into the deposit. This is similar to the situation at Sunstone Butte, he remarked.

Anticipating higher demand, he also planned to cut more frequently in 2015. Rather than cutting two to three times per year, he will cut 2,000 to 4,000 kg per month (new production plus stockpiled rough), depending on his needs. As 4,000 kg equates to approximately 2,000 carats of finished stones, Woodmark expected his production to significantly increase market availability of Oregon sunstone in 2015.

Like all the Oregon sunstone mines, Ponderosa produces a substantial quantity of yellow and near-colorless labradorite—material with little or no pink or red and no visible coppery reflections. One of the things Woodmark has learned at this show is the importance of cutting style and quality on a gem’s perceived value. He sold 2 kg of yellow rough to another vendor at the AGTA show—Ken Ivey (Ivey Gemstones, Prescott, Arizona)—and was astonished at the result.

Ivey’s use of concave cutting styles (figure 6) presented the feldspar’s bright yellow color far more effectively than conventional cuts. With conventional cutting, Woodmark struggled to get a few tens of dollars per carat for yellow goods. With only a modest investment in extra cutting costs for concave faceting—perhaps twice the expenditure—the same material can sell for up to five times as much. As the yellow rough sells for a couple hundred dollars per kilogram, this is a potentially significant value addition in the finished product.

Another encouraging trend Woodmark sees is that designers and jewelers are mixing calibrated sunstones of different shapes and colors in the same jewelry piece. The casting is standardized, but because every combination is unique there is no longer the need to match them. Volume business with sunstone jewelry has always been hampered by the perception that every stone in a piece has to match and every piece must be uniform.

In Woodmark’s opinion, even home shopping channels like QVC are moving away from that concept, in essence marketing the uniqueness of the gem rather than a uniformity it can never provide. He cited a piece for which he supplied 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0 mm calibrated gems. One was a top-quality red sunstone, and the others were paler pink. In this way, the manufacturer does not have to match the stones and can use larger volumes.