Queensland Opal Fields: Home of the Unique Australian Boulder Opal

January 24, 2017

INTRODUCTION

As Lighting Ridge is the home of fine black opal, Queensland's opal fields are the home of boulder opal, which has become more widely known by both the industry and consumers. Boulder opal has exceptional play-of-color, but it also has more to show; collectors and consumers appreciate its exotic patterns, abstract imagery, and unique structural relationship with its host rocks. In June 2015 a GIA team visited three boulder opal fields in western Queensland and extensively recorded the different aspects of the industry related to this special gem.

THE EARLY OPAL INDUSTRY

Salable precious opals were first obtained from the mines near Listowel Downs Station around 1870. A jeweler from Toowoomba, Herbert Bond, played an important role in developing the early opal industry in Queensland. By 1875 the discovery of a series of deposits in Kyabra Hills in South West Queensland had attracted Mr. Bond’s attention. With all the treasure recovered from the fields, there was no market in which to sell the stones, so in 1879 Mr. Bond organized some mine owners to form an opal syndicate before taking the stones to London for sale. In London he floated a company for £2500. While his first attempt at establishing a market failed, Queen Victoria noticed his efforts. A big fan of opal, she granted him a 40-acre freehold land lease of the famous Aladdin Mine, the only one in that part of Queensland at the time.

not actively mined anymore due to drought or lack of salable production. The GIA team

visited Koroit, Yowah, and Quilpie, three actively mined areas, and met many opal miners.

It took another 10 years for opal to win over the gem consumers in London. By the 1890s, through the efforts of Tullie Wollaston, an Adelaide gem dealer, opal was so popular that the sale of diamonds declined. Opal’s popularity eventually agitated the competitors, articles were published to tell the public that opal could bring bad luck, and the stone lost its market in London due to the negative press. The consequences of this notorious manipulation still influence England’s opal market today.

THE BOULDER OPAL FIELDS

There are more than a dozen opal fields in central Queensland. The state is extensively covered by the opal-bearing Desert Sandstone formation of Upper Cretaceous age, with more than 300,000 km2 of land available for exploration and potential mining. While Queensland also produces opal in vesicular basalt of Cenozoic age, none of the deposits are of commercial value similar to the boulder opal from sedimentary rocks. The authors visited three opal fields: Koroit, Yowah, and Quilpie. Though the fields have many commonalities, each is distinguished in its own way.

KOROIT

Located in the Cunnamulla Mineral District, Koroit lies about 77 km north-northeast of Eulo. The Desert Sandstone formation extends in roughly a north-south direction for at least 129 km , with an average width of 16 km. Opal was first discovered in Koroit in 1897, when a syndicate was formed by the manager of Tilbaroo Station. This discovery caused a small opal rush at the Koroit field.

The most recent development of the Koroit field was in the 1970s. Today Koroit is one of the best opal-producing areas in Australia. The authors visited a mine owned and operated by Mark Moore and his business partner. Mr. Moore is a part-time boulder opal miner and a part-time surf coach. This operation has both open-pit and underground mining. The open pit provides a perfect profile of the local stratigraphy. Ironstone concretions of different sizes are contained in the soft sandstone layer. These concretions need to be sawed or cracked to expose the opal. Opals are also found along linear structures as seams.

The underground operation is small-scale. Mr. Moore uses the same type of digger we saw in Lighting Ridge. A very clear fault line can be spotted in the underground mine. Mr. Moore follows structures such as faults to look for opals. Here he collected several pieces of boulder opal samples for GIA’s reference collection.

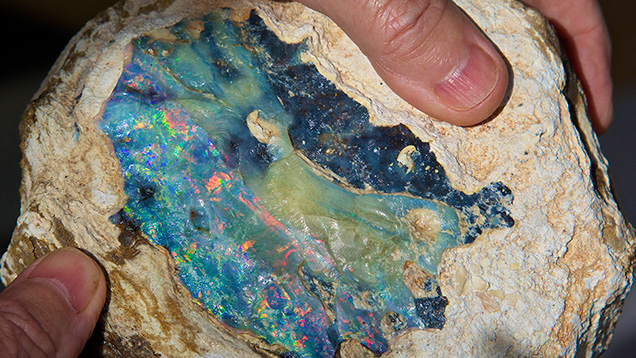

Boulder opal from Koroit has brilliant play-of-color. The authors enjoyed looking at and recording some of the most stunning samples that Mark had collected over time. In addition to mining, Mark also cuts and polishes some of the best production he has on-site. A workshop for opal polishing is next to his house.

YOWAH

About 10 km southwest of Koroit is the town of Yowah. The first opal mining lease in Yowah was registered in 1884. By 1902 the population of Yowah had reached 100. The Southern Cross Mine and the Great Extend Mine are two of the most famous names in Yowah’s history. Today the town is still very opal oriented, with open-pit and underground mining operations all over the fields. Opal tourism is the town’s main industry. Opal tours, shops, and fossicking activities are some of the most eye-catching sights.

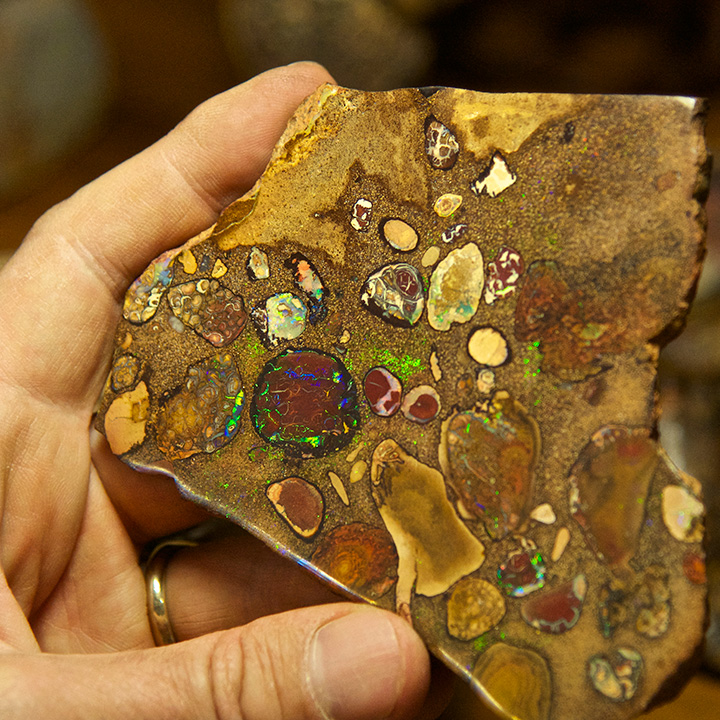

In Yowah opal is found mostly in siliceous ironstone concretions, but it also occurs in other forms, attached to the ironstone or sandstone. The ironstone concretions are found within the pinkish soft lower strata of the Desert Sandstone formation. Multiple concretion-containing beds can be found within the sandstone layer. The authors were amazed by the divining rods used by some of the mine owners to explore opal deposits. Bulldozers are used to cut open deposits and transport materials. Agitators of different scales are used to stir the materials. The concretions are sawed or cut to expose the opal inside.

The most characteristic boulder opals from this field are called “Yowah Nuts.” These nuts are ironstone concretions ranging from peanut size to lemon size, with precious opal formed as the kernel of the concretions. The volume and brilliance of this type of boulder opal are astonishing. The authors were lucky to see a giant boulder opal extracted from the host’s mine just two days before. This opal was of bright bluish play-of-color. When asked about the future of this rough, the owner said he wished to donate it to a museum.

QUILPIE

Quilpie is another town well-known for boulder opal mining and trading. The first discovery of opal in this area was at Bull Creek in 1885, north of the current township location. The mining department has an office in the town center where visitors can get fossicking permits. Opal jeweler Mark Anthony Hodges hosted us in his opal store on the main street. He showed us stunning boulder opal jewelry with stones mined in Quilpie and finished locally. In his backyard was a large quantity of boulder opal rough waiting to be processed.

Leaving Quilpie, we headed about 65 km north to Alaric, where Eric Stelzer and his family own and operate a large-scale open-pit opal mine. The open pit provided an astounding profile of the local stratigraphy.

From bottom to top there are two divisions within the Desert Sandstone formation. The soft opal-bearing sandstone and clays underlie the extremely hard reddish siliceous rocks, which are 4.5 to 15 meters thick. The hard rocks work as a cap to protect the rocks below them. With a very high weathering and erosion rate, a large amount of the Desert Sandstone formation has decomposed. The remaining portions are now seen in the field in different forms, such as low ranges, tablelands, and isolated flat-topped hills occurring at frequent intervals. From above the local topography is very similar to the well-known Basin and Range region in North America.

Opal is recovered in the siliceous ironstone concretions ranging from centimeters to meters in diameter or occurs as seam or replacement of plant fossils like trees. Most materials are processed and polished on-site by the family. According to Mr. Stelzer, opal is mined predominantly in the soft sandstone layer, but he did work on a colluvial deposit immediately next to the open pit years back. Due to opal’s relatively low hardness, secondary deposits are extremely rare. If the erosion was fast and recent enough, small amounts of stones can be found close to their source. The authors did see a landslide on the slope of the flat-top hill being cut and mined.

THE BEAUTY OF BOULDER OPAL

Queensland opal fields produce the most spectacular opal of all different kinds. Boulder opal is the vast majority of the production and the most characteristic. The opal part is the same in nature as those found in other opal fields, and the boulder part is usually ironstone and/or sandstone. On many occasions the precious opal is spread out through cracks in its host rock or just attached to the surface of host rock as a thin layer; therefore it is not practical or even possible to separate it from the rock. The miners choose to leave them in the host rock and polish them together as one piece.

This way the miners can keep the finished product durable while at the same time showcase the best play-of-color and/or pattern. A thin layer of opal might not be astonishing, but with the host rock as a dark-colored background, the play-of-color can be enhanced. The shape and structure of the host rock also add fun to the finished product.

Along with being set in jewelry, boulder opal can be displayed in more creative ways than you can imagine. In Yowah the authors were honored to meet Eddie Maguire, a boulder opal collector and true artist. Mr. Maguire generously shared his collection, knowledge, experience, and understanding of opal. Each item in his collection is sliced or polished in a different way. The authors had never before seen such a display of boulder opal. Mr. Maguire also made wood carving supports for many of them, which reminded the authors of similar supports commonly used in displaying jade carvings.

EPILOGUE

The last day we spent at the Stelzer family’s opal mine began with a beautiful sunrise, followed by a ride in an ultralight airplane for everyone in the group. In this manner our visit to the Australian opal fields drew to a close. As we flew over the opal fields, all the good memories of this magical gem and people came alive once again. We had all been stung by the “opal bug,” as opal expert Len Cram had named it.

Dr. Tao Hsu is technical editor of Gems & Gemology; Andrew Lucas is manager of field gemology for education at GIA Carlsbad; Vincent Pardieu is senior manager of field gemology at GIA Bangkok.

The authors would like to thank Terry Coldham for his guidance during their visit.