Centuries of Opulence:

Jewels of India

October 11, 2017

Large flawless diamonds from the Golconda region. Rich green emeralds from Colombia. Blood-red rubies from Burma. Only the most visually striking would do, set in the purest gold. For more than 5,000 years, jewelry has played an integral role in the history of India. Wars were fought and empires won and lost in pursuit of these riches.

Yet, because of cultural practices, relatively little of the historic jewelry exists, the gems and precious metals repurposed by succeeding generations. The jewels in “Centuries of Opulence: Jewels of India,” which will be on display in Carlsbad until October 10 2018, are on loan from a private collection and showcase more than 300 years of adornment in India from the 17th to the 20th century, including several from the magnificent Mughal Era (1526–1857).

In fact, it was a thirst for the fabled riches of Northern India that drew Babur, the Muslim founder of the Mughal Empire, from Central Asia. Lavishly adorned with the jewels they had won, received as “gifts” or created from the vast stores of gems and gold in their treasuries, the Mughals and other rulers of India continued to honor the religious, metaphysical and social importance of the precious materials and the forms they took.

Intricately designed pieces celebrated Allah and Hindu gods, such as Shiva, Krishna and Vishnu. Other jewels were integral to the marriage contract, as seen in the elaborate wedding necklaces, in depictions of snakes or fish as symbols of fertility, and in nose rings worn as testament to happiness in the union. Brightly colored gems and enamel symbolized the forces of life: red as blood, the life force of the animal kingdom; green as the plant life created by the blue sky combined with the yellow sun. To this day in India, gems and jewelry carry potent messages of power, honor and love.

Journey of the Gem

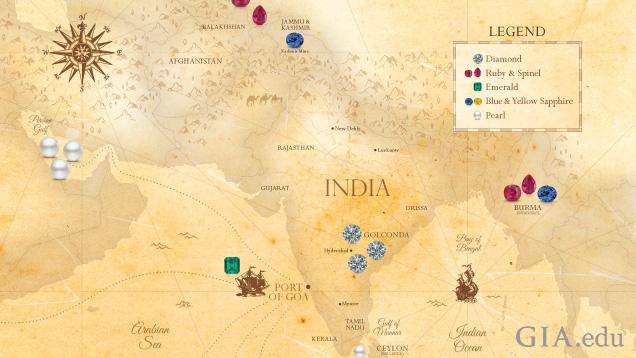

What did these adventurers hope to get in trade? Nothing less than the most beautiful diamonds in the world from what was long the only source. Some of our most celebrated diamonds—including the infamous Hope and Koh-i-Noor—originated from India’s famed Golconda mining area. The Indian aristocracy kept the best for themselves and traded the balance for emeralds, rubies, sapphires, spinels and pearls from all corners of the earth.

Quality was paramount. Only the finest gems and purest gold would evoke maximum power to honor the gods and serve as talismans to ward off evil. Gemologists were valued members of most royal courts in India. The Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (reign 1658–1707) had three in his entourage: one to care for the gems, a second to estimate their value, and the third to grade them and detect treated gems or imitations. Gemological knowledge was passed from father to son for generations, but also taught in texts such as the notorious Kama Sutra.

Today, GIA conducts research and educates thousands to continue this tradition of expanding and perfecting gemological knowledge: investigating how gems form and establishing clues to their origin from some of these fabled sources.

Golconda Diamonds

“The treasury has its source in the mines;

From the treasury the army comes into being.

With the treasury and the army, the Earth is obtained. . . .”

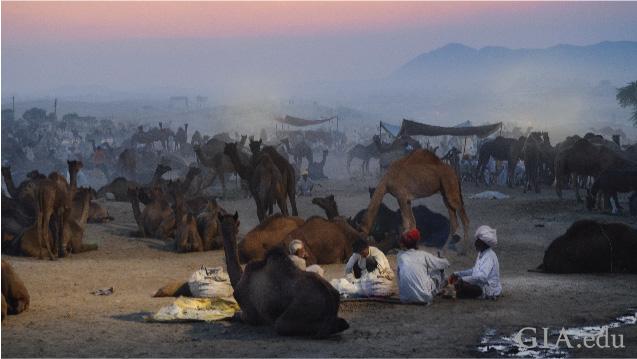

So wrote Indian statesman Kautilya in his 4th century Arthashastra, a how-to guide for managing an empire. Since antiquity, the most important mines were diamonds. And the most ancient of India’s three main diamond-producing areas were near the legendary fortress city of Golconda. The exact locations were a closely guarded secret that promised a horrible death for any who revealed it. Golconda was the center for trade in diamonds, launching caravans as large as 10,000 camels and oxen to travel across Asia.

According to the Indian life science Ayurveda, wearing a diamond will guarantee long life, endurance and beauty. The thin, flat diamonds seen in historical Indian jewelry are typically slices cleaved from the original rough, many with flat facets polished around their edges. Not until the 19th century did brilliant cut diamonds begin to appear in India, as finished stones and faceting techniques arrived from Europe.

Many spectacular diamonds originated from Indian mines. These include the legendary 105 carat Koh-i-Noor Diamond, now in the British Crown Jewels, and the ill-fated 45 carat blue Hope Diamond, which brought misery to many before Harry Winston donated it to the Smithsonian Institution in 1958.

Today, the Golconda mining region is largely exhausted. It is estimated that the Indian mines produced at least 12 million carats over more than 2,000 years. Yet even as these mines waned, the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in the early 1700s and then South Africa in the late 1860s brought a continued supply to India’s royal connoisseurs.

Spinel and Ruby

Red. Blood. Without it no person can survive. This symbol of power, life and youthful energy was represented by two major gems in Indian jewelry: spinel and ruby. For much of India’s history, these two very different gem minerals were almost interchangeable. The earliest magnificent red gemstones were spinels carried over treacherous mountains from Balakhshan (Badakhshan), an area that extended from today’s northern Afghanistan into Tajikistan and gave spinels the name “balas rubies.” Indeed, Great Britain’s 170 carat Black Prince’s “Ruby” and 352 carat Timur “Ruby,” both believed to originate from Balakhshan, are spinels. Curiously, in an early gem treatment, the centuries-old Black Prince’s stone, pierced for wear as a pendant, features a ruby plug in the original hole. Following a common practice in India, the massive Timur is inscribed with the names and dates of six owners, starting with Shah Jahangir, 1612.

Rubies were also found in Afghanistan, but the main sources for this red variety of corundum during the Mughal Era were the gem island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the bountiful Mogok area of Burma (Myanmar). Most ancient Indian jewelry features the well-rounded, waterworn rubies found in these secondary, alluvial deposits that were simply polished to reveal their rich color. Primary deposits in Mogok were not exploited until the 19th century, when miners dug downward to reach the white marble where the red crystals formed as a result of contact metamorphism.

Emerald

Green is a powerful life force in India. The most coveted green gem was emerald, the vibrant green variety of the mineral beryl. Early emeralds were brought primarily from Egypt’s legendary “Cleopatra’s mines,” found in the hills inland from the Red Sea. But these stones were typically pale and heavily included.

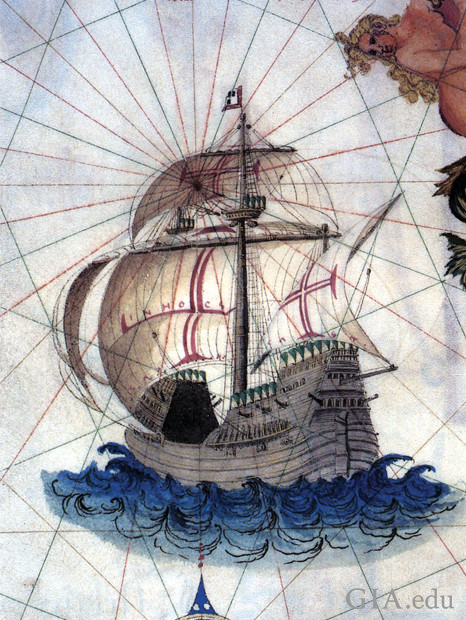

Coincident with the rise of the Mughal Empire in the 1500s, Spanish soldiers in South America conquered the warlike Muzo tribe and took control of their emerald mines in the lush green jungles of what is today Colombia. Galleons laden with emeralds from the Muzo and later Chivor mines sailed the brutal Atlantic Ocean to Spain. The finest of these alluring green gems entered the king’s coffers or were sold to Portuguese merchants, who carried them to India’s coastal trading center of Goa—and on to the royal treasuries. Over time, emeralds were brought in from other countries, such as Afghanistan and Brazil, but none surpassed the finest emeralds from Colombia.

A British trader who stayed in the palace at Agra from 1609 to 1611 reported that Shah Jahangir had more than half a million carats of unmounted emeralds in his treasury, so coveted were the rich green gemstones coming from the New World. Today, the city of Jaipur is the world’s center for emerald cutting, a vestige of India’s long passion for the gem.

Blue and Yellow Sapphires

In many cultures, blue sapphire is revered as a source of wisdom, prophecy and power. In ancient Hindu astrology, though, blue sapphire was linked to the dark and turbulent planet, Saturn. If not handled properly, blue sapphire could cause problems for the wearer. As a result, many avoided it altogether. Yellow sapphire, however, promised wealth, intelligence and good health.

To be effective, sapphires had to be eye clean. Reports of heat treatment to enhance clarity—sapphires were packed in clay and placed in fire for hours—date back to the 16th century. Although sapphires were known from South India since at least the 4th century, most originated from Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The alluvial gravels of this “jewel box of the Indian Ocean” have been producing bright, transparent gems for more than 2,000 years.

Traders also carried fine sapphires from the Mogok region of Burma (Myanmar), with the blue corundum crystals even larger than their ruby cousins. In 1881, a fortuitous landslide high in the Himalayas exposed a large pocket of velvety “cornflower” blue crystals. At first, itinerant merchants had to be cajoled to take the stones, which they traded for salt, weight for weight. As the spectacular sapphires began to appear in the south, the Maharaja of Kashmir—and his army—took control of the new locality. Thousands of large, beautiful crystals were recovered, but production was sporadic; today there is little organized mining in that region.

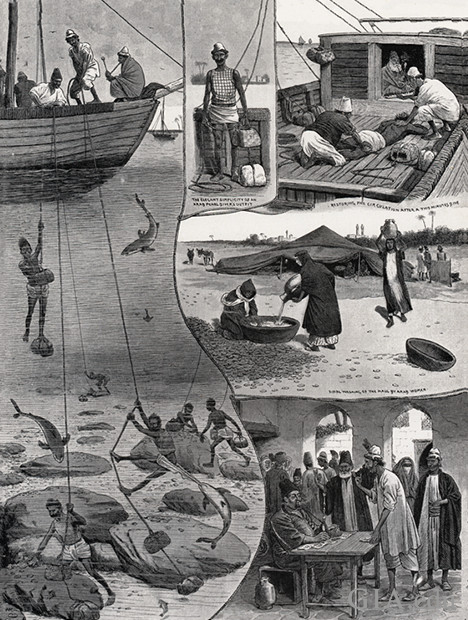

Pearls

Imagine heading out to sea in a small boat, then being weighted down and dropped into shark-infested waters more than 100 feet deep. Holding your breath until you’ve filled the net around your neck with mollusks, and ascending as fast as possible, you gasp for air as you break the surface. Then you repeat the dive 40, 50, 60 times a day, hoping—usually in vain—that at least one of those mollusks will reveal a round, white, luminous pearl. For centuries, this was the life of the countless pearl divers in the Arabian (Persian) Gulf and the Gulf of Mannar, India’s chief sources of pearls.

Yet pearls were fundamental to the royal treasuries of the Mughals and maharajas. Important symbols of power, they were worn as jewelry, sewn onto clothing and used to embellish household and religious objects. Only the finest pearls—the whitest, the roundest, those with the best orient—would bring optimal good fortune: a long life, riches and forgiveness for one’s sins. The ancient trading center of Basra, in modern-day Iraq, offered the best Arabian Gulf pearls; the name Basra is still associated with the highest-quality natural pearls.

By the 1600s, overfishing had decimated the oyster beds in the Gulf of Mannar. For a time, pearls from the New World (off the coast of Venezuela) helped satisfy India’s insatiable appetite for this organic gem. Eventually, though, this source and the pearl banks of the Arabian Gulf were also largely depleted. Not until the 20th century did technology bring an influx of cultured pearls to every corner of the world. Today, more than ever, a fine natural pearl is an object of rarity and desire.

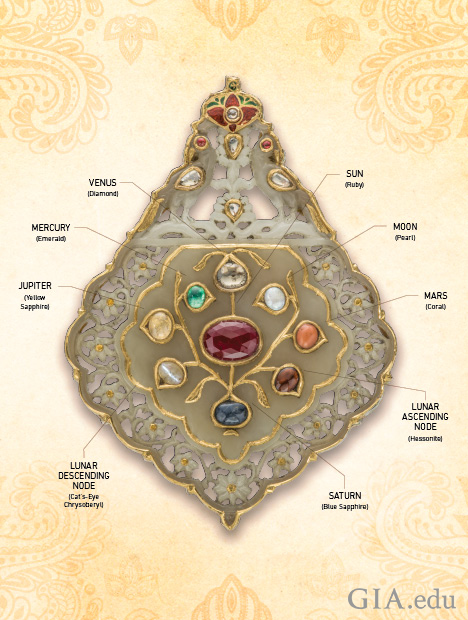

Navaratna Gems

(nephrite), diamond, emerald, treated ruby, blue sapphire, yellow sapphire, pearl, coral, hessonite and cat’s-eye

chrysoberyl in 22K gold ▪ 8.5 x 12 cm. Photo by Robert & Orasa Weldon/GIA

Worried about your livelihood? Suffering from a chronic illness? Desperate for money or power? The navaratna (“nine gemstones”) was one of the most powerful talismans in the Hindu religion, one that was eventually adopted by Muslims as well. The nine gems represent the celestial bodies of Indian astrology—Sun (ruby), Moon (pearl), Mercury (emerald), Mars (coral), Jupiter (yellow sapphire or topaz), Venus (diamond) and Saturn (blue sapphire)—and the rising (zircon or hessonite) and descending (cat’s-eye) nodes of the moon.

Set in jewelry in a prescribed arrangement, they protect the wearer from the negative energies of the planets and strengthen the positive benefits of the different gems, bringing good health, wealth, mental strength and wisdom. When the gems are set in a circular pattern, the ruby (sun) is traditionally in the center, as it represents the center of the solar system. As quoted in S. M. Tagore’s Mani-mala, all the gems “must be high-born and flawless.”

At the time navaratna was introduced, believed to be during the 10th century, all these gem materials were found on or near the Indian subcontinent. In fact, India’s history of diamond mining and pearl fishing extends back more than 2,000 years; in ancient times, large portions of its coastline were protected by vast coral reefs. Today the eastern state of Orissa alone produces ruby, sapphire, emerald (beryl), garnet, topaz, zircon and cat’s-eye chrysoberyl. The gems of navaratna represent the natural treasures of this ancient civilization.

Special Exhibit at GIA in Carlsbad

View these gems and jewels at GIA in Carlsbad from October 13, 2017 to October 10, 2018.

GIA World Headquarters

The Robert Mouawad Campus

5345 Armada Drive

Carlsbad, CA 92008

Please schedule your tour at least 24 hours in advance.

Alice Keller is the Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Gems & Gemology at GIA Carlsbad. Terri Ottaway is the Museum Curator at GIA Carlsbad.

GIA is very grateful to the private collectors, who wish to remain anonymous, for the loan of the pieces in the exhibit and their help editing the text and captions. Tsajon von Lixfeld G.G. introduced the collectors to GIA and also provided his expertise for the text and captions.