Solid Laboratory-Grown Single-Crystal Diamond Ring

Carved single-crystal diamond rings are rare, with few examples to reference (see Spring 2020 Lab Notes, pp. 132–133). But with advancing technology in the laboratory-grown diamond industry, the creation of solid faceted diamond rings is now a reality. Recently submitted to the New York laboratory was a 4.04 ct single-crystal laboratory-grown diamond ring (figure 1). The 3.03 mm thick band had an inner diameter of 16.35–16.40 mm and an outer diameter of 20.32–20.40 mm. The ring was produced by Dutch Diamond Technologies in collaboration with the Belgian jewelry store Heursel, established in 1745.

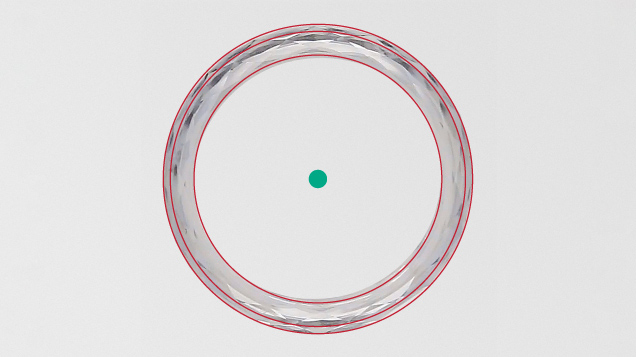

This laboratory-grown diamond ring was cut from an 8.54 ct plate grown by chemical vapor deposition (CVD). Laser cutting produced a near-perfect circular ring, as demonstrated using digital imaging analysis to measure its inner and outer circumferences (figure 2).

The manufacture of a solid single-crystal diamond ring is a complex and challenging process. Once material is removed from the crystal, very fine fractures and imbalanced strain can have severe consequences, and the ring can shatter. Processing can take more than six months. Creating the ring from a single-crystal laboratory-grown diamond involved about 1,131 hours of processing (including pre-grinding) in the Dutch town of Cuijk, followed by 751 hours of polishing in Belgium.

Infrared absorption analysis revealed it was a type IIa diamond (no detectable nitrogen), and no hydrogen-related peaks were detected at 3107 or 3123 cm–1. Photoluminescence spectroscopy showed interesting vacancy-related defects indicative of a multi-step growth process. A very strong emission from the silicon vacancy (SiV–) defect was observed with 633 nm laser excitation; this is a common feature used to identify CVD-grown diamond. The conclusion was that this ring had not undergone post-growth treatment; nevertheless, it was notable that the ring showed relatively low nitrogen-related defects such as NV centers, along with no detectable 468 nm peak or the 596/597 nm doublet. P. Martineau et al. (“Identification of synthetic diamond grown using chemical vapor deposition (CVD),” Spring 2004 G&G, pp. 2–25) observed the 596/597 doublet with a 514 nm laser. Also of note, there were no H3 or 468 nm centers detected with 457 nm laser excitation.

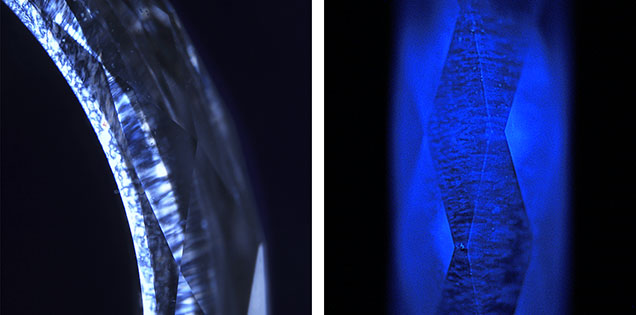

Strong birefringence was observed using cross-polarized light under microscopic analysis, with an unusual radial pattern (figure 3, left) signifying unique growth conditions compared to typical CVD diamonds available in the market today. The deep ultraviolet illumination of the DiamondView (figure 3, right) confirmed these unusual growth features with a lack of post-growth fluorescence colors such as green produced by the H3 center.

The solid laboratory-grown diamond ring was studied by GIA and determined to have VVS2 clarity based on dark non-diamond carbon pinpoint inclusions (growth remnants typical of CVD-grown diamonds) with Good polish (polishing on the interior surface of the ring precluded Very Good). Although the ring was a near-perfect circle (figure 2), symmetry was considered not applicable. The diamond had an E color specification based on GIA’s color grading scale. The ring was laser inscribed “Laboratory-Grown” on a side facet.

The quality and size of this solid diamond ring (see the video below) provide a great example of the advancing technology in laboratory-grown diamonds and changing trends in the jewelry industry. This is the first time a GIA laboratory has examined a colorless diamond ring fashioned entirely from a laboratory-grown diamond.